Riley Lorgus (BA ’24)

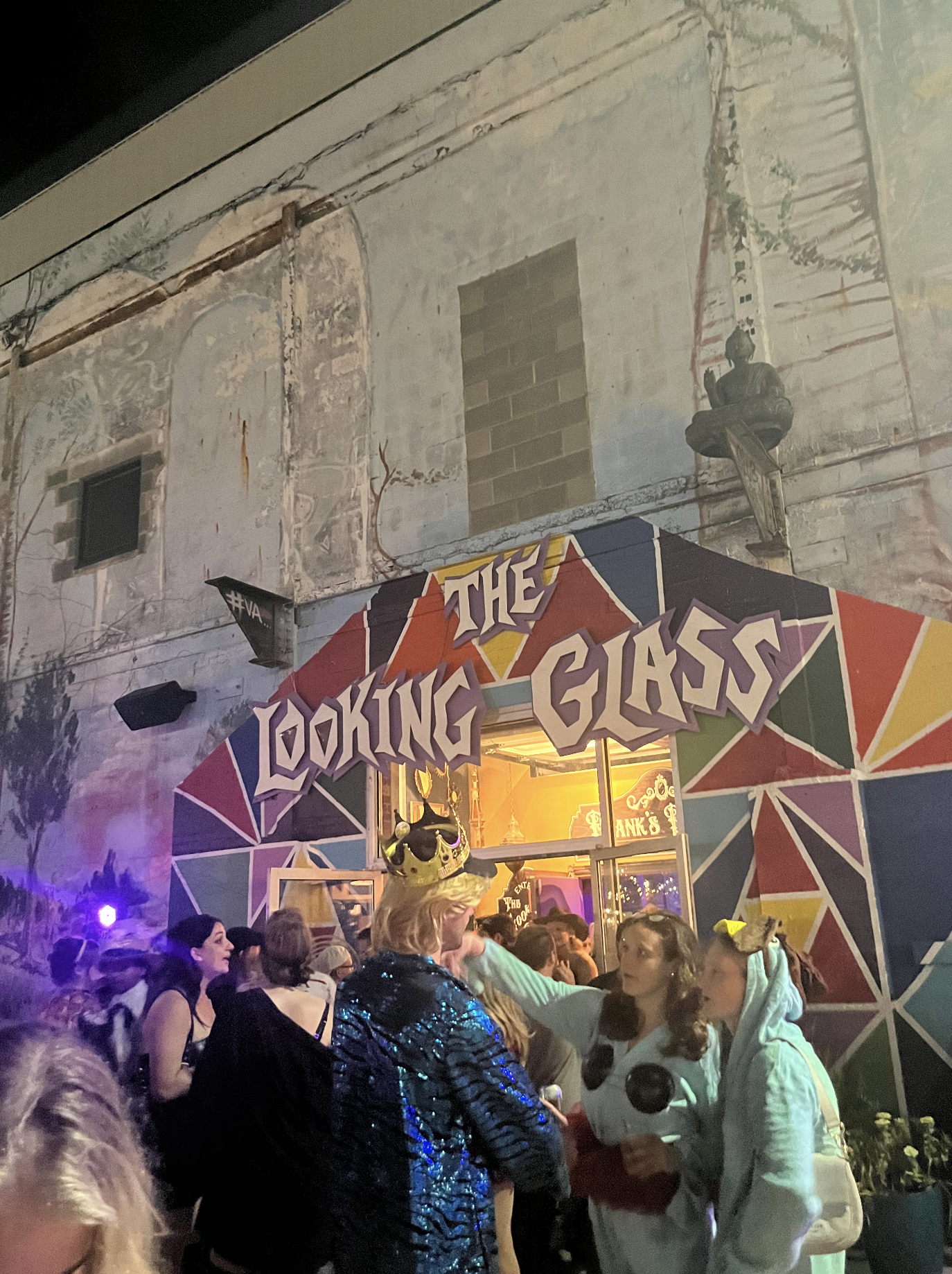

As the semester comes to a close, the Lighting of the Lawn (LOTL) committee is excited to invite the UVA community to the 22nd Annual Lighting of the Lawn. This beloved University tradition will be held this Friday, December 1, from 7 to 9:30 p.m. at the Rotunda. LOTL is open to the entire University as well as the wider Charlottesville community. As we count down the days until LOTL, we hope that you will join us this upcoming Friday.

Doors to the event open at 6 p.m. with a performance from the undergraduate band Weekends and Wednesdays on the South Lawn, accompanied by food trucks, photo stations, free snacks, hot beverages, and so much more. The performances begin at the Rotunda stage at 7 p.m. and feature student dance and acapella groups, with the signature light show as a finale (which will feature a few more songs this year!).

LOTL was born from the terrifying events of September 11, 2001. Following the national tragedy, an air of sadness, fear, and grief remained on Grounds. Seeing their once joyful community now overwhelmingly scared, a group of student leaders came together during that dark fall season to uplift the community. Members of the Fourth Year Trustees Committee of the Class of 2002 were determined to uplift and unite the community in any way possible. Trustee Matt West proposed the idea of bringing light, literally, back to Grounds by illuminating the lawn with string lights. As soon as the University administration and Facilities Management team got on board, students got to work hanging lights on the Rotunda and Pavilions before the very first Lighting of the Lawn on December 15, 2001.

What started out as a modest event has grown exponentially in the years since the first LOTL. Today, this cherished event draws over fifteen thousand attendees across the University and Charlottesville community. With performances from over twenty-five student acapella and dance groups, receptions across the Lawn, and the iconic, colorful light show, LOTL is a huge celebration of love, light, and people we hold dear to our hearts. What remains consistent each year is the universal message of unity and community as we gather together before the fall semester draws to a close. As always, LOTL is planned entirely by a dedicated group of undergraduate students, who share the same determination to illuminate Grounds as the 2002 Fourth Year Trustees.

LOTL has adapted to our recent history and experiences as a community. As we pass the one-year anniversary of the tragic deaths of our peers D’Sean Perry, Lavel Davis Jr., and Devin Chandler, this year’s Lighting of the Lawn remains committed to celebrating their lives and the light that they brought to our community. Their numbers, 41, 1, and 15 will be illuminated during the event.

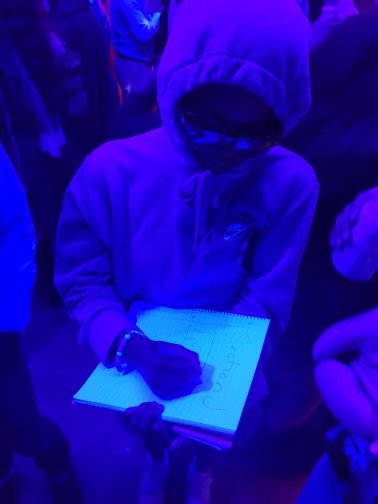

This year, we would like to invite the community to join us at the Disglow! The LOTL committee designed this night of Disglow fun to celebrate the spirit of community, the joy and strength that is found in togetherness. Despite hardships faced by members of our community, LOTL shines bright and is a beacon of hope for those at the University, the Charlottesville area, and even attendees joining us virtually. We hope this year is no exception. What is more joyful than a night of glow-in-the-dark disco fun? Wear your brightest disco outfit and bring your glow sticks to the Lawn. Our night at the Disglow will uplift the community and celebrate their hard work during the fall semester.

More information on this year’s Lighting of the Lawn can be found at our website lightingofthelawn.com or on our Instagram page @lotluva.

The LOTL committee has put in countless hours of tireless work during the fall semester to put on this event. All of us on the committee hope to see you on the Lawn and we can’t wait to celebrate with you!

---

ral8pd@virginia.edu