UVA Law’s Lost Histories: The Landmark Case of Gregory Swanson

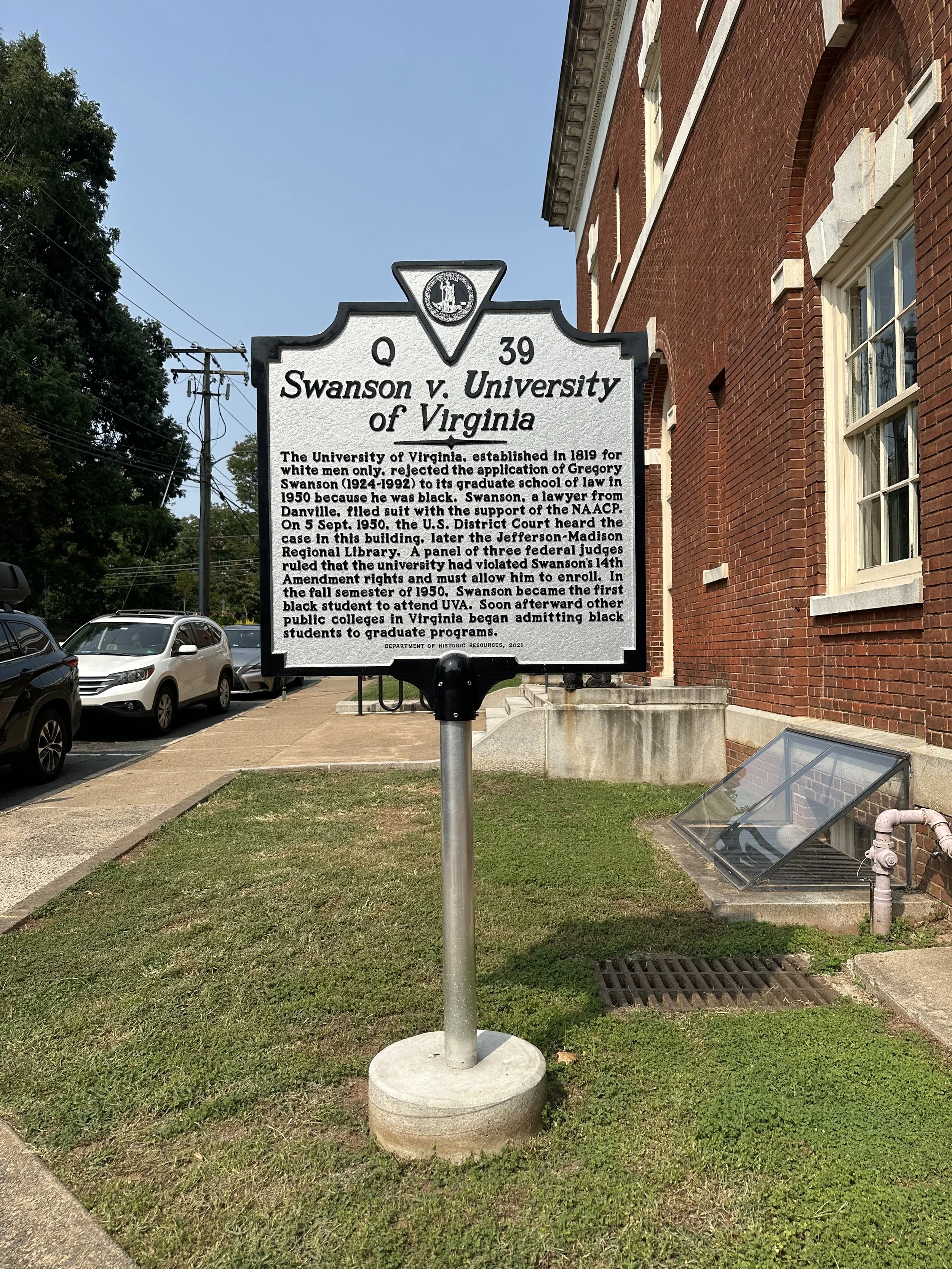

Historical marker at the Jefferson-Madison Regional Library in downtown Charlottesville, Virginia.

Source: Photo taken by author.

This article is the first in a two-part collaboration piece covering the Gregory Swanson commemoration program that took place on September 5, 2025, and an interview with Albemarle Commonwealth Attorney James Hingeley. Both articles discuss the history and life of Gregory Swanson, the man who integrated UVA, becoming the first African American admitted to any all-white university in the Old Confederacy. September 5, 2025 marks the 75th anniversary of the Swanson decision that was handed down on September 5, 1950, by the federal court sitting in Charlottesville. The court order required UVA to admit Gregory Swanson to the law school as a graduate student, making Swanson the first African American admitted to UVA. Notably, the UVA Law faculty at that time unanimously supported Mr. Swanson’s application for admission. The Board of Visitors, however, opposed Swanson’s admission, despite the prevailing Supreme Court rulings in Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950). In response—and with the support of the NAACP, including Spottswood Robinson, Oliver Hill, and Thurgood Marshall—Gregory Swanson filed suit, and on September 5 the court ordered that Swanson be admitted to UVA over the objection of the Board of Visitors. Part one of this two-part series features the interview with James Hingeley.

Nicky Demitry: Thank you so much for taking the time to talk about this story with me today! My first question—this seems like a pretty personal event and story to you. What is your involvement or history with this program and with Mr. Swanson?

James Hingeley: Well, the Gregory Swanson story was lost to history. I was a member of the Swanson Legacy Committee, which, at least ten years ago now, worked hard to bring the story to the attention of the Charlottesville and the UVA communities. I got involved in it through a good friend of mine, Evans Hopkins, the nephew of Gregory Swanson.[1] I was acquainted with Evans and he took the initiative to try to increase the awareness of the Charlottesville and UVA communities of this historical case that happened right here in Charlottesville. So I was involved in helping to tell a story from years and years ago. And it's just a fantastic story which excites me to be a part of . . . helping spread information about Gregory Swanson and that decision in our community. So that's kind of what motivates me.

ND: That’s amazing.

JH: And I have a maybe funny anecdote that you might enjoy as a law student. And I can tell the story because it's been repeated publicly by Risa Golubuff after we had our first Swanson Legacy program. I don’t know exactly when it was, but ten years ago, perhaps—at least in that range.

We had that program at the same place that this program is going to be on Friday, which is in the now-Jefferson-Madison Regional Library downtown. But at the time of the Swanson decision, it was the actual federal courtroom where the case took place. It was on a Sunday afternoon, and we had some guests who were coming in from out of town. Some of the guests were family members of Mr. Swanson and got lost here in town. I don't know if this particular guest was family or not, but anyhow, some of them were downtown in Charlottesville, coming to the program and looking for the library.

They're unfamiliar with Charlottesville. They aren't from here. And it so happened, as these things do, that Risa was downtown and happened to be running around, and this person from outside of town struck up a conversation with her and said, “Hey, can you tell me where the library is? I'm going to a program there.”

And Risa was interested in the program and said, “Oh, what are you going to? What was this program?” And she told Risa that it was a program relating to Gregory Swanson, to this great civil rights case. And Risa, who was at that time a law professor— this is before she would be Dean of the Law School—and already a very well-known civil rights historian, didn't know about the Gregory Swanson story.

So that kind of proves my point that this was . . . lost. This decision was lost to history. And so Risa became one of the people who was instrumental in telling the story and bringing it to the Law School. And now there is a Gregory Swanson award that's given periodically. It was at one of those award ceremonies at the Law School that Risa told the story that I just told you, which is why I can say it. Because she said it publicly, as a way of letting people know that if you didn't know about the story, that was not really exceptional. She didn't know about it. She's a civil rights historian.

So, anyhow, we told the story. We’ve had several programs. The Law School took up the cause and it now has a portrait of Gregory Swanson, which is hanging in Clay Hall. And do you know when you walk into the library?

ND: Mmhm!

JH: As you go in on the left, there's a display, it's called a timeline. And Gregory Swanson is in that timeline, along with some rotating artifacts of his.

And we keep doing this program. That's what we're doing now. This Friday, it happens to be the 75th anniversary of the Gregory Swanson decision, which was handed down on September 5, 1950, seventy-five years ago. So those of us who were involved in planning this program thought that this would be another good occasion on which to tell the story and keep the story of Gregory Swanson alive.

Now, here's part of the story that I particularly appreciate, being a University of Virginia Law School graduate. And that is: In 1950, when Gregory Swanson, an African American, applied to the UVA Law School, the UVA Law faculty unanimously agreed to his admission.

Sometimes some people hear, oh, UVA turned him down. They don't get the full picture. The full picture is UVA Law School, which is the school he applied to, said yes. Which I think—in 1950 before Brown v. Board of Education and other big civil rights cases in our country—I think that shows that the Law School faculty in a Southern university was pretty far ahead of the times. And the leading advocate on the Law School faculty at the time for Swanson's admission was Mortimer Caplin. And that's a name that's well known to people in the Law School. Mortimer Caplin has been a great benefactor to the Law School, but he also has the distinction, in my mind, of being the leading advocate on the Law School faculty in support of Gregory Swanson and in his admission to law school.

Now, as it happened, the Board of Visitors said no in the face of the Law School's agreement to accept Swanson. And it was the Board of Visitors’ refusal to admit Gregory Swanson that led to the lawsuit, which we are now commemorating. So that's one aspect of it. Another aspect of it that really excites me is that the Gregory Swanson decision was part of the coordinated strategy of the NAACP that unfolded over many years to break down Jim Crow segregation in the United States. This wasn't just a single case that popped up. This was part of that overarching strategy. The NAACP assisted Gregory Swanson in the lawsuit—of course, they helped to set it up because this was part of their strategy. And the NAACP lawyers who came to represent Gregory Swanson included Thurgood Marshall, Oliver Hill, and Spottswood Robinson.

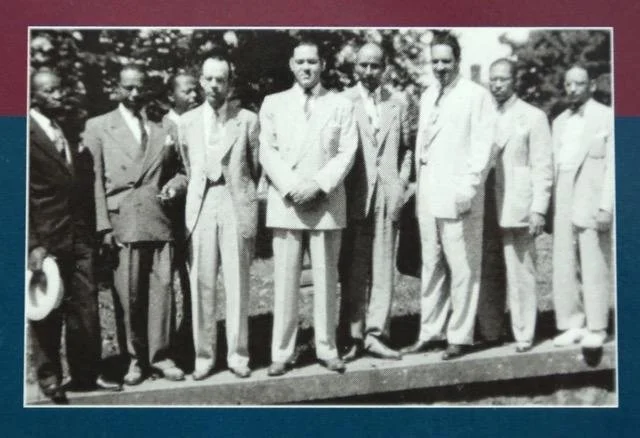

These legal giants of the civil rights era, who all were here in Charlottesville, represented Gregory Swanson, and I have that picture—the picture of them all standing outside the courthouse in Charlottesville on the day that the decision was rendered. And so that's an aspect of it that's really an important part of the history. So first of all, the Law School’s acceptance of his application, and second of all, this case fitting into the NAACP strategy to break down the segregation barriers of our society at that time. I think it is really important and valuable for people to know that this was part of a big plan.

ND: It’s incredible. I didn't . . . I mean, I knew the timing of 1950, but it didn't sink in that this was all taking place before Brown v. Board. I mean, the University was still fully segregated, right?

JH: Yes, that was the point! Fully segregated.

ND: Wow.

JH: This was the first African American admitted to UVA, and in fact, the first African American admitted to any all-white university in the Old Confederacy. And of course, the case set the precedent that the Constitution required—well, I don't want to interpret the law, because I haven't read the decision recently, but—the general principle was laid down that you cannot deny somebody admission because they’re African American.

Now, we could deny your admission because of the pretext that you're unqualified or something else. But the baseline rule, it seems to me here, is that the U.S. Constitution says, in 1950 before Brown v. Board of Education, that you cannot deny somebody admission because of their race.

ND: Yeah. Wow. I know he also applied as an LLM—

JH: Yes.

ND: Was that part of the NAACP plan, as a more strategic avenue somehow? Or was it just because he’d already graduated from a law school?

JH: The reason was that he was already a lawyer. And he was interested in getting an advanced degree of law so that he could teach in a law school. So he was a little unusual in the sense that he was seeking admission as a graduate law student. But he was also somebody who at this time in his life made a good test case. I mean, they could have gotten somebody who just finished college, I suppose, who was interested in starting law school at the basic level. But–

ND: It would have been even more difficult, that makes sense.

JH: He was recruited. It was all part of their strategy. He [Swanson] was just 26 years old.

The individuals depicted in the photograph taken on the edge of (then-named) Lee Park on Second St. in Charlottesville are, from left to right (front row only): Dr. Jessie Tinsley, Martin A. Martin, Spottswood Robinson, III, Gregory Swanson, Oliver W. Hill, Sr., Thurgood Marshall, Hale Thompson, and Robert Cooley.

Source: Oliver Hill Family via James Hingeley

[1] Evans Hopkins is a civil rights activist who wrote his memoir, Life after Life: A Story of Rage and Redemption, while serving a life sentence in prison. He also wrote extensively about the experience of incarceration, publishing articles in the Washington Post while still actively incarcerated, until his parole in 1997. See https://www.npr.org/2005/05/11/4647771/life-after-life-author-evans-hopkins for more information.