Did Lawyers Still Have to Close Probates in the Third Reich?

I am studying for the February bar exam[1] at a moment when it feels, at best, surreal and, at worst, deeply unserious.

I spend my days memorizing doctrines that presume good faith, neutral administration, and a shared commitment to the rule of law while watching those assumptions collapse in real time. There is a peculiar dissonance in dutifully committing to memory the elements of due process while observing how optional due process has become. And there is a particular existential absurdity in studying the law as a woman in 2026: watching groups like the Heritage Foundation seriously propose eliminating no-fault divorce[2] and access to contraception,[3] while I sit at my desk taking notes on property laws written in a time when women didn’t even have a defined legal identity as individuals.[4] But I’m sure my knowledge of Virginia’s adoption of the Uniform Statutory Rule Against Perpetuities will help! Fascists hate when you know this one trick![5]

This is not the first time lawyers have found themselves calmly performing legal rituals amid moral catastrophe. History is not subtle about this. Lawyers continued to draft wills, close probates, and file conveyances during the Third Reich.[6] Courts functioned. Property changed hands. Estates were administered. Paperwork was filed. I assume people like me whined. The machinery of law did not grind to a halt when injustice became official policy; it adapted, as it always has.

American legal history offers no refuge either. Under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, lawyers, judges, and clerks across the North enforced a system that required private citizens to assist in the capture of escaped human beings. Courtrooms processed claims of ownership over people with procedural efficiency. Judges applied precedent. Lawyers made arguments. The law worked. Nor did this machinery disappear with emancipation: Jim Crow segregation was not a lawless aberration but a meticulously constructed legal regime, sustained by courts, legislatures, and lawyers who translated racial domination into doctrine.[7] Dred Scott v. Sandford and Plessy v. Ferguson did not emerge from a legal vacuum; they were the product of a jurisprudence that treated exclusion, hierarchy, and unfathomable cruelty as legally coherent from the very beginning. So why are any of us surprised to see the infrastructure of the legal field not just turn a blind eye, but directly and openly profit from that same abject cruelty?[8]

This is the uncomfortable truth legal education often gestures toward but rarely confronts head-on: the law has never been a reliable engine of moral progress. It has been a technology of order and of state-sanctioned violence. Sometimes that order coincides with justice. Often, it does not.

And yet, law students are taught—implicitly, and sometimes explicitly—to believe that the law trends toward fairness, that its arc bends toward equity if only we reason well enough, argue persuasively enough, or cite the right case. For many of us, particularly white students raised on a civics class version of constitutional reverence, this belief is not just professional—it is personal. The Constitution is framed as a sacred text, not a contingent political document. The courts are described as guardians, not institutions staffed by fallible people with incentives, ideologies, and blind spots (an overly generous assessment).

Studying for the bar while watching administrative cruelty justified through technocratic language makes the mythology harder to sustain. When legality becomes a substitute for legitimacy, when procedural compliance is treated as moral absolution, the gap between what the law is and what we were told it meant becomes impossible to ignore. What makes this moment especially destabilizing is not that the law is failing to live up to its ideals—that has always been true—but how naked that failure has become. There is less effort now to pretend that enforcement is neutral or that discretion is evenly applied. The language of legality remains intact while its substance disappears: fundamental rights are ignored, court orders are brushed aside,[9] and the point is continually driven home that there is nothing we can do.[10]

The legal profession responds, as it has so many times before, with tepid paperwork instead of a reckoning, instead of accountability. What do we do when it becomes blindingly obvious that the law is a paper tiger? That it has teeth only for the most vulnerable? There has always been a fragility to the law in America, particularly in our highest court.[11] But is it time to finally acknowledge openly that the fragility is by design? And when can we tell if it’s finally broken, particularly when that judgment call is fundamentally perspectival?

Annoying rhetorical questions aside, I’m not trying to say that the law is irrelevant—at least, not yet. If anything, it may matter enormously, just not in the way I imagined when I started law school. The law matters because it reveals, with brutal clarity, who holds power and who does not. It matters because it can launder cruelty through procedure, because it can operate smoothly while inflicting profound harm. And it matters because, in this moment, it is stripping away the face of constitutional democracy and exposing a rot that has always been present. That rot—the reality of deep injustice, cruelty, and institutional apathy—has never been evenly distributed or evenly acknowledged, but it is now becoming harder to ignore.

It is worth remembering that the authors of The Federalist Papers were notably pessimistic about the survival chances of republican government. It is also worth remembering that the authors of those papers drafted the damn things anyway. If the law has always been contingent, political, and deeply shaped by those who wield it, then progress has never come from passive faith in doctrine. It has come from pressure, exposure, resistance, and refusal.

So the law has not suddenly failed us, but its pretenses are eroding. The facade is harder to maintain when contradictions are visible to everyone. When legality and justice diverge so openly, the question becomes unavoidable: what do we want the law to do, and who do we want it to serve?

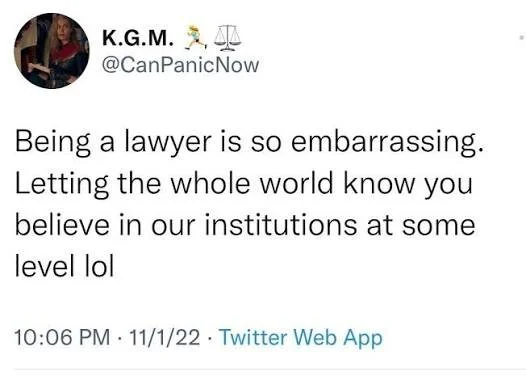

For those of us entering the profession now, that question may be the only honest starting point. Studying for the bar under these conditions feels absurd because it is, but it is also instructive. It forces a reckoning with the reality that being a lawyer has never guaranteed moral alignment. The work has always required choice.

If there is hope here, it lies not in nostalgia for a constitutional purity that never existed, but in the possibility that widespread disillusionment might finally puncture the reverence that has insulated unjust systems from critique. Maybe seeing the law as it actually operates—rather than the simulacram we were taught to admire—creates room to imagine something better. Not perfect. Not neutral. But more accountable, and genuinely committed to the idea that equality before the law must be more than a recital on an exam. The law must exist to safeguard society from the consequences of absolute power, because Lord Acton’s famous warning that, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely,” is more relevant than ever. If our legal system can no longer serve that function, then it may be time to consider what must replace it.

I will keep studying. The law is not a panacea, and I don’t know whether it will protect the people I care about. I’m no longer expecting miracles, but I’ll keep my faith in meliorism. What remains is a choice: to stay attentive to the human consequences of the rules we apply, to resist the comfort of narratives about inevitable progress, and to remain human inside a system that often rewards detachment. If nothing is guaranteed, then the refusal to become empty matters. We choose to be advocates not because it promises victory, but because it preserves something essential. If the law does not care, then we must. As one of my favorite science fiction authors put it, “There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.”[12]

[1] Shoutout to my Feb 2026 bar exam homies. There are dozens of us! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lKie-vgUGdI.

[2] Samantha Chapman, Attacks on No-Fault Divorce Are Dangerous – Especially for Those Experiencing Domestic Violence, ACLU. (October, 2023) https://www.aclusd.org/news/attacks-no-fault-divorce-are-dangerous-especially-those-experiencing-domestic-violence/.

[3] Rebekah Sager Heritage Foundation issues report on ‘America’s family crisis’, Pennsylvania Independent (January 2026), https://pennsylvaniaindependent.com/politics/heritage-foundation-report-families-marriage-education-infertility-fetal-personhood/

[4] Is it foreshadowing? And now for a brief sidebar from a banger: “Freedoms of speech permitted to women could be considered a catalyst of the Salem Witch trials in 1692. The results of the Salem trials proved the greatest preventive of any future outbreaks in the court system.” Marilynne K. Roach, The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-by-Day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege 572 (2002).

[5] Did you know that Virginia courts do not impose a limit on the number of depositions you can take, whereas federal courts cap you at 10 without leave of court? (You’re welcome, Virginia bar takers, for this amuse bouche of bar prep.)

[6] Cynthia Fountaine, Complicity in the Perversion of Justice: The Role of Lawyers in Eroding the Rule of Law in the Third Reich, 10 St. Mary's Journal on Legal Malpractice & Ethics 2, 198 (2020).

[7] Doctrine that provided inspiration for Nazi Germany’s Nuremberg Laws– The Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor. See How the Nazis Were Inspired by Jim Crow, https://www.history.com/articles/how-the-nazis-were-inspired-by-jim-crow.

[8] Lizzie Bird, LexisNexis’s Contract With ICE As Unjust Enrichment, 95 Colorado Law Review 4 (2024) https://lawreview.colorado.edu/print/volume-95/lexisnexiss-contract-with-ice-as-unjust-enrichment-lizzie-bird/; Stephen Fowler, DOJ releases tranche of Epstein files, says it has met its legal obligations, NPR (January, 2026), https://www.npr.org/2026/01/30/nx-s1-5693904/epstein-files-doj-trump.

[9] J. Patrick Coolican, Federal judge — a Scalia protege — again rips ICE for ignoring court orders in Minnesota, Minnesota Reformer (January 2026), https://minnesotareformer.com/briefs/federal-judge-a-scalia-protege-again-rips-ice-for-ignoring-court-orders-in-minnesota/.

[10] And on that note, my favorite documentary has only gotten better with age. See Adrienne Matei, Systems are crumbling – but daily life continues. The dissonance is real (2025), https://www.theguardian.com/wellness/ng-interactive/2025/may/22/hypernormalization-dysfunction-status-quo ( about Hypernormalisation).

[11] Clay Jenkinson, Anatomy of the Supreme Court as an Institution in Crisis, Governing (May 2023) https://www.governing.com/context/anatomy-of-the-supreme-court-as-an-institution-in-crisis; Tara Leigh Grove, The Supreme Court’s Legitimacy Dilemma, 123 Harvard Law Review 8 (June 2019) https://harvardlawreview.org/print/vol-132/the-supreme-courts-legitimacy-dilemma/.

[12] Octavia Butler. And on the topic of her works, this brief article is very salient right now, despite being 26 years old: Octavia E. Butler, A Few Rules for Predicting the Future (2000) https://commongood.cc/reader/a-few-rules-for-predicting-the-future-by-octavia-e-butler/.